An invisible hero for invisible victims: interview with domestic violence pioneer, Erin Pizzey

Domestic violence can have devastating effects on mental health, not only for the victims, but for children who witness domestic violence too. It’s such an important social issue that if you were told that someone was the pioneer of domestic violence services in the UK, you would expect them to be a recognisable figure, if not a household name. Erin Pizzey founded the first battered women’s shelter (now called Refuge) in the modern world in 1971, but was marginalised from her organisation because of her support for male victims, and was not invited to Refuge’s 50th anniversary celebrations a few weeks ago. So if the name Erin Pizzey isn’t instantly recognisable to you, then welcome to the topsy-turvy world of domestic violence provision, where not only is the key founder invisible, but around a third of the victims – the men - are invisible too.

John Barry (JB): Your celebration dinner in London recently, which launched the Erin Pizzey award, was fantastic. What was the high point of that event for you?

Erin Pizzey (EP): Firstly, I was really honoured and grateful, and secondly what stood out completely for me was the piper. I just couldn't believe he was so wonderful. I was being pushed by Derek in my wheelchair and the piper wailing behind me. It took place in a lovely venue, beautiful surroundings, fantastic meal and the wine was really good. It was a marvellous evening

JB: What kind of people will be nominated for this award?

EP: The award was set up by Deborah Powney and Rick Bradford, and will be given to people like me who actually fought to make changes. It will be given every year, and there will be a dinner to celebrate. There will be a huge number of people who've never really been heard of because they were airbrushed out of history.

JB: Speaking of airbrushed from history, I saw some of the media coverage of the 50th anniversary of Refuge, and was thinking to myself ‘where's Erin in all of this?’

EP: This goes back to 1971 when the emerging feminist movement in England hijacked the narrative. I had said from the very beginning that the roots of domestic violence stemmed from the family and were intergenerational. This was the case in my own family, with my great grandparents, grandparents and my parents. My father was emotionally abusive, but my mother was physically abusive, and beat me with an ironing cord. I showed the teacher the lashings on my legs, and she said ‘you deserved it - you are a terrible child’. The idea that you could be at a terrible child because you were having a terrible childhood was not properly recognised back then.

“90% of men in prisons have come from generational family violence… So when they're violent - which is what they've learned - we then perpetuate the violence by putting them in prison.”

When I opened the refuge in 1971, I knew from the beginning that it wasn’t just men. Of the first 100 women, 62 were as violent as the men they had left. These women were the most important to change. Instead of going from frustration straight to raging fights, they needed to learn, and that was the point of the refuge - to teach. And it's not difficult, if we would only learn to [cope with frustration] and, if we did learn it, it would empty the prisons. 90% of men in prisons have come from generational family violence - the same would apply for women - and they've never been offered any other model. So when they're violent - which is what they've learned - we then perpetuate the violence by putting them in prison. But we're not going to punish battered children because they're not experiencing anything that hasn’t been done to them already.

JB: We have the Duluth model for the men, and for the women we don't have anything. Is that fair to say?

EP: The Duluth model has been redundant a long time ago. It was made by a male feminist. Basically, what it does to men is humiliate them. For a start, even before they do the [Duluth] wheel they have to admit to their ‘male privileges’ - what a meaningless statement - so fortunately it has been completely disregarded so that isn’t really on service at the moment.

“One woman who was the governor of a prison said to me that ‘every child born into a violent family is a point on my pension’.”

There is no approach to taking care of women. What they do to women with a history of violence is to take their children away. What happens is the ‘family mafia’ of agencies simply get more clients. One woman who was the governor of a prison said to me that ‘every child born into a violent family is a point on my pension’.

JB: That’s pretty cold.

EP: That shouldn’t be the way it is. We don't offer any intervention to people who grow up in a violent family. This is why the refuge was always full of good, gentle, men. The intervention has to be a mentor, somebody you can up look up to, like I did when I was nine. I went to a holiday home while my parents were abroad, and I saw Miss Williams. She was a golf champion, she drove ambulances during the war. She had this children’s holiday home and I looked at her and I thought ‘that's who I want to be’, and she saved me.

JB: So a mentor can replace a parent?

P: It doesn’t replace the parent at all. All a mentor does is give you a vision of what you could be. I witnessed a lot of empty arguing between my mother and father, and always swore I would never be like that, I would never lift my voice. And I've tried to do that, but it was Miss Williams who showed me. She was a gentle giant - she was 6 foot 7 - she had 25 children in her care in this very big old manor, and nobody ever crossed her, and she didn't raise her voice. Every night when the children lined up in the hallway to say ‘goodnight Miss Williams’, she would say ‘goodnight’. She had a very good way of thinking - I was really obnoxious and very violent as a child - and she would say ‘Oh well Erin, if you can't control yourself how about you do the washing up for a week’. Well, washing up for 25 children, you quickly learned that you don't want to do that.

JB: The Mayor of London is proposing mentors for boys who have gone off the rails. Do you think this will be successful in reducing gang violence?

EP: Yes I do. I have spoken with boys who are in care and who are fatherless or who have fathers who are rotten, and yes it could make a huge difference, but that's only if it is a real mentoring, and that means an all day mentoring because you are asking this child to change their practice. When you are a child, the thing you have to quickly work at is how you are going to survive in this atmosphere. I chose violence, but some children choose hibernation and it's much worse for them really because they store up stress and end up with migraines, outbreaks of the skin and even stomach ulcers.

JB: I suppose a lot of these boys will come from families that experience violence or coercive control; could an all day mentor break that cycle? Does ‘all day’ mean ‘seven days a week’, or.?..

EP: It has to be an available relationship where the child needs to learn to trust. In a violent family, they will not trust. Remember it’s more likely to be women who are more violent than fathers. The safest place for a child is with its biological father, because after mothers as abusers the next worst is stepfathers, or boyfriends of the mother. We have to really see that those people can change, and we need to apply that rather than just try to jail anybody who abuses children.

JB: Going back to adults, it sounds like men don’t get help whether they are victims or perpetrators. Is there any way that men can help themselves, if they're not giving getting help from services?

EP: Well no. There are vast sums of money given to the feminists, something like £300 million per year. The Mankind Initiative will help men as victims but they get peanuts. Families need Fathers (FNF) will help in custody cases, but get peanuts. I'm patron of both of those. We need to actually recognise that fathers are just as important as the mothers, and that where parenting is failing we need strategies for survival for parents, and not punishment.

JB: Should men seek anger management from a therapist or go to Mankind Initiative for help…?

EP: Therapists are extremely expensive, so [contact] the Mankind Initiative or Families need Fathers.

JB: Feminist groups are now offering help to male victims of domestic violence. Do you think that man can't be helped by these feminist organisations?

EP: If a man phones on a hotline, before long he finds he is on a perpetrators programme whether he is innocent or not. And one of the problems with the perpetrators programmes is that if he does not do the course, he cannot have access to his children. So if he does the course he has to admit that he is violent, even if he is not. So it's a stick and carrot, isn't it.

JB: Or stick and stick. I didn't realise that if a man phones up these…

EP: There are two organisations. Refuge is the one that was taken from me, and the National Federation is a different organisation, but they do the same thing. They are both feminist organisations. I don't think people know that boys over the age of 12 can't go into refuges. Did you know that?

JB: I think I saw an interview where you said that, and it's been like that for a long time, hasn’t it?

EP: It’s always been like that because of the feminist mantra that all women are innocent victims of males, therefore by the time they become twelve they are pubescent, and then violent.

JB: So these families groups have got the idea that men are inherently violent, or inevitably violent due to socialisation?

“The only reason they ever agreed to have anything to do with men is because they were told that they wouldn't get their grants if they didn't, under the Equalities Act.”

EP: They are [said to be] toxic, and what do you think that does to a boy? Young men who go to lectures are told how not to be a rapist.

JB: So can feminist organisations help men in any way? It sounds like they could do more harm.

EP: I agree. They are harmful towards men. The only reason they ever agreed to have anything to do with men is because they were told that they wouldn't get their grants if they didn't [help men], under the Equalities Act. What needs to be done is that all the money needs to be shared equally between programmes for men and women. You would see that the feminists would leave very quickly, with the proper professionals being left to take over. If organisations for men and women shared equally the money, you would find the feminists would leave, because the sharing would have to also be part of the therapy, [recognising] that men and women were capable of being violent.

JB: Could this sharing happen any time soon?

EP: It should, but we would have to then deal with the likes of Jess Phillips and Harriet Harman [Members of Parliament], all of them who - because they want votes - claim that they are feminists. The majority of women will say of course ‘I am a feminist’. But they're talking about equality between men and women - which I agree with - but what they don't understand is what they're actually signing up to is a movement that has nothing to do with men, and sees men as toxic and dangerous. It's a terrible message to give our little boys in school. You know, toxic masculinity includes boys.

JB: Is there any way this situation could change?

EP: You would have to just bring in the Equality Act and make it work, and say that every organisation that gets money for domestic violence has to sign up to the fact that both men and women are equally capable of being violent.

JB: So it would be enforcing the law as it already exists. Is there anybody in politics who would be willing to take up that cause?

“Men have got to get up and be counted. A lot of this is because men don't argue with women… I think it is very patronising to say that we have to be specially catered for because we are women, and therefore we can't be criticised.”

EP: Philip Davies is a very good man. All he wanted was International Men's Day. But Jess Phillips told him that every day is men's day. He said that after he had spoken in the House and he was outside in the bar, men were sidling up to him saying ‘You are very brave. I agree with you, but I don't dare say it publicly’. Men have got to get up and be counted. A lot of this is because men don't argue with women.

JB: Why do you think that is, and how can this reluctance be overcome?

EP: Men would have to change the way they approach women. It isn't equal and I think it is very patronising to say that we have to be specially catered for because we are women, and therefore we can't be criticised. But you know, men are frightened of women, I have always said that. When they have been standing on the doorstep in the refuge, I’ve said ‘you have to actually be able to communicate with your wife - you can't go on pretending that what she does is alright’.

JB: And what are men frightened of?

EP: Well these days, you argue with your partner, women pick up the phone - I have seen this happen - and say that you have sexually assaulted her, you have battered her, and the police come around and take the man away, and they don't listen to what he's got to say.

JB: Then surely men are right to be scared of women, if women have so much power.

EP: But how many men's groups do you see doing anything about it?

JB: And what can be done about it, would you suggest?

EP: Stand up and tell the truth, that men and women can be equally violent.

JB: Should they talk to each other in the pub, or talk to their MP, write them a letter….? What needs to be done in practical terms?

EP: Essentially in practical terms it’s about human relationships. We have to go back to the beginnings. We teach sexual relationships in school but we don't teach emotional relationships. I remember there were 900 students in this huge place I was talking to, and everybody was very nervous because the students could be very rowdy, but I just walked on and said ‘how many of you have been hit by a girlfriend?’ You could have heard the silence. ‘How many of you had in your relationship a partner who is morbidly jealous, in other words always fantasising about you having gone out and having sex, even though you know she knows perfectly well you are not’. And these are all terrible signs of instability in relationships. It's interesting because I always said in the refuge, the boys as children are damaged by domestic violence by their parents, one or both, but boys particularly if the mother is promiscuous. It doesn't mean that you can't have transcended it, but…

JB: Back to men seeking help. It is often said that men don’t want to talk about their problems. What can the average man do to improve things, if not for themselves but for other men…?

EP: Join the Mankind Initiative, or FNF, or men’s groups, and that will make a difference. You can talk to other men in the same situation. All that gives a men strength. A woman doesn’t lose anything if she gets rid of a man. She keeps the house, kids, income - he loses everything. The majority of men who are homeless on the street are there because of alleged domestic violence.

“If I asked men to build a bridge you would do it tomorrow. If I asked them to take care of each other, most would not know what I was talking about. Men are not used to caring for each other.”

JB: I have heard that men sometimes join these groups, but then drop out. Sometimes they join to help with their problem, but once that is addressed, they don’t come back to support other men. Is there any way of getting men to stay engaged, supportive?

EP: Some men will stay, but if you think about it, men have always made their relationships through a woman. It’s her friends, and then it’s his friends. They go to ball games with their men friends, or maybe the pub, but the majority of all their relationships are with other women. And that’s got to stop. Men’s groups are very small compared to womens’. If I asked men to build a bridge you would do it tomorrow. If I asked them to take care of each other, most would not know what I was talking about. Men are not used to caring for each other.

JB: Social identity theory studies have found that men don’t treat each other as ‘an ingroup’. So although all other identities will bring people together, and having a common identity will lead to ingroup favouritism and bias against ‘outgroups’, this doesn’t happen with men. It happens with women though, and in fact men will tend to favour women more than men.

EP: What men do is live their lives through the woman. You ask women and get out and march and protest for something they want, and you get thousands of women. The last men’s march? 100 men turned up.

JB: Given social identity theory, do you think there is much hope of building men’s groups like women’s groups?

EP: There's a chivalrous gene in men, and this is part of the problem.

JB: It's interesting that you called it a chivalrous gene because it suggests there is something ingrained in a man, in which case it is quite hard to change. If women want to band together to change laws to help women…

“All this education is basically abusive because what it tries to do is feminise boys to make them more like girls.”

EP: I saw it happen 50 years ago. I warned people and nobody listened. It's even worse in America, because the women had all that time to insinuate their policies into the laws everywhere into education. All this education is basically abusive because what it tries to do is feminise boys to make them more like girls. Little boys do not want to please women teachers, but there aren't any male teachers. I taught reading to remedial kids in school for a year just to find out what happens to boys, and of course it was boys who were having trouble reading because they didn't want to read the kind of girly books that they were supposed to read. So I found some extremely good books. One of them is called My Brother’s Exploding Bottom, and the boys ripped through them. There is no provision for boys in our society or for men. Hariet Harman said in a policy paper in 1990 that the new family would be women and children. She also said that men were not necessarily harmonious to family life.

JB: has that policy paper influenced many laws and legislation…?

EP: Of course. It's interesting because feminists have been let loose into law, so many of them are barristers and solicitors. What they have done is to expand the laws of domestic violence to such an extent that if he doesn't give her whatever money that she wants, that’s domestic violence; you raise your voice, that’s domestic violence. It doesn't hold for women, but it holds for men.

JB: So are you saying that men need to speak up and get together and support each other in these groups.

EP: It will be historic if they do, but it will have to happen. I don't know how much and how many times men have to suffer abuse for being men, ‘toxic males’, until they finally get it together and understand that they have to get together and make changes themselves because otherwise… The only time, feminists say, you need men is to go to war. Otherwise they are expendable, expendable as fathers. Even though any of us who know about families know that fathers are hugely necessary. Warren Farrell says that for generations now we have had fatherless children. When the father is present in the family, the girl will menstruate much later and is much less likely to get pregnant [at a young age]. These are facts you never hear about.

JB: The Boy Crisis is very good on this. You have written quite a few books, both fiction and non fiction. Do you have a particular favourite, or one that you think people should read in order to understand these issues?

EP: Prone To Violence is the one that there was a huge march against. I was at a lunch at the Savoy for women, and they were all outside with this huge banner saying ‘Erin Pizzey condones male violence’. I had to have a police escort all round England when I published that book. It's hard to get hold of now. You can get it second hand on Amazon. It’s about the treatment programme for violent women and it's a tough read because you are reading about awful abuse of the women who came to the refuge, and some were innocent victims, but the majority were victims of their own childhoods, basically. I would ask people to read that book.

JB: You have been through a lot of tough times yourself, suffered all sorts of abuse, and even homelessness. How did you cope through the tough times?

EP: God. I have this personal relationship and I have always, since about the age of four and a half, been aware that God is in my life and there was nothing that could happen to me without his permission. What was brilliant about so much of it is when you look back, those trials you went through had a purpose to them. Not only do you learn, but other people can learn too. I used to say to the mothers ‘everything that you've been through, it's like a PhD, a social work course you've done’. What was so marvellous was that so many of them who went back to their own communities then got involved in helping others.

JB: Neil Lyndon who received terrible abuse after his critique of feminism, No More Sex War, found his faith to be of enormous importance in helping him through.

EP: That’s very true. I had a terrible breakdown after Refuge when I lost it. I ended up in Charing Cross Hospital for three months and I just remember, you know, when Jesus despairs of the cross, well I remember that moment when I had basically gone down this terrible, terrible, dark hole and my feet touched - physically - the ground, and then this voice said to me ‘There is only one way, and it's up’. And that's when I decided ‘Ok - I'm coming back’.

JB: Fantastic. it reminds me of the saying, I don't know who said it, but it's about when people have so much suffering in their life they eventually ask in frustration, ‘where is God?’ And the answer, according to the quote, is ‘at the end of your tether’. The problem of course is that we have a high male suicide rate, so maybe some men don’t find God at the end of…

EP: Yes, but suicide is to do with abandonment issues, and I've always said that the seeds of suicide begin very early. My grandson committed suicide, and I'm building a foundation with Rita Wright, whose daughter committed suicide. Because we don't understand it and we don't do anything about it, and we need to. I know that after he died, I tried to find organisations that would help me and all I could find was other grieving families who also had nowhere to go. So we're starting a foundation to actually help, or first look into ‘why suicide’. I have said it from the very beginning when you get what I call ‘primary pain’, and this happens very early in childhood. It can be something quite simple, like mummy goes into hospital and the child is too young to understand - because they won't let the child into the hospital - where mummy has gone, and that's the beginning of feelings of abandonment. Or a father can leave the family and walk out and that's when the children feel abandonment. They may recover from that and go on for years and years and then suddenly something happens, and that's when they commit suicide.

JB: Interesting. Martin Seager, who was at the launch of the Erin Pizzey award, has developed an idea about ‘ruptured attachment’. It sounds quite a similar thing. Certainly The Centre for Male Psychology would be happy to work with you on anything to do with male suicide. But to wrap things up, is there any last thing you would like to say to the people reading this article?

EP: I would like all agencies to be especially alerted to when children are showing signs of damage at school, because they tend just to write it off. My teacher said to me I'm a terrible child, but if you've got a terrible child, then how is the child terrible? Children are not born vicious, so ask the right questions and get the right help for children as early as you can, with health visitors visiting houses.

Conclusion

Despite having faced unbelievable levels of harassment, Erin Pizzey has been one of the most steadfast, fearless supporters of male victims of domestic violence worldwide. The fact that for decades her role has been airbrushed out of the history of domestic violence support tells you all you need to know about how intense the gender politics is in this field.

Three points stand out in this interview. Firstly, male victims need to speak up in defence of themselves more, and learn to support each other more. Secondly, we need to be more aware of the signs that boys are under duress, and be aware of the impact on them of popularised notions such as ‘toxic masculinity’. Thirdly, domestic violence services have become more about access to funding than about supporting victims or reforming perpetrators. As long as taxpayers’ money is going to groups who don’t recognise female perpetration and apparently aren’t interested in understanding male perpetration, the misery of domestic violence will roll on and on without any end in sight.

Biography

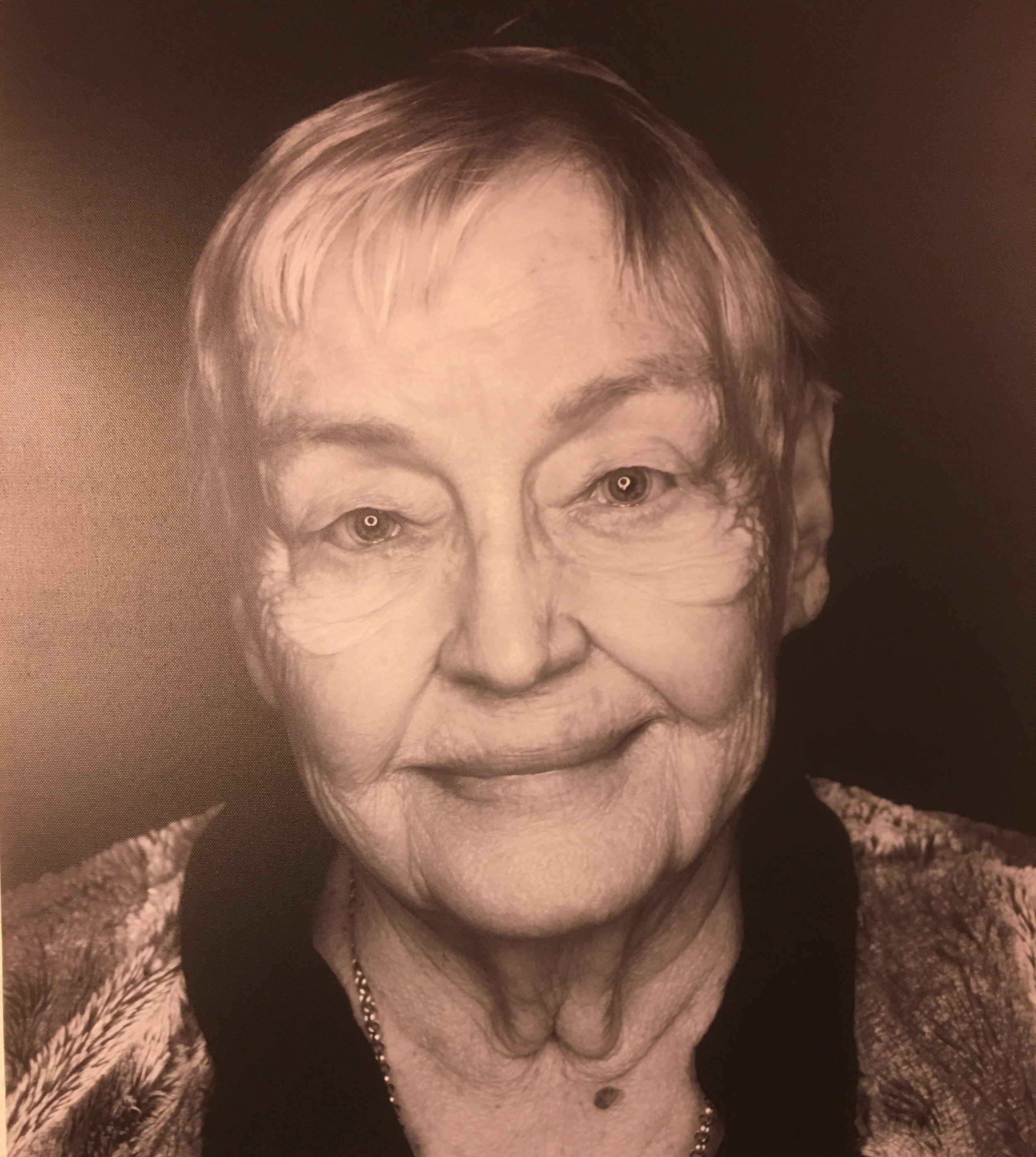

Erin Pizzey started the first and largest domestic violence shelter in the modern world, Refuge, in 1971. Her recognition of male victims of female violence led to a split from the feminist movement, and years of harassment followed. She is the author of several books, and in 2021 became the first recipient of the Erin Pizzey award for services to all victims of domestic violence.

Further information

If you are a man experiencing domestic abuse, you can call the ManKind Initiative helpline weekdays 10am to 4pm on 01823 334244. If you are interested in finding out more about this field, seek out Pizzey’s book Prone to Violence and see the ManKind Initiative’s statistics on this issue.

Scroll down to join the discussion

Disclaimer: This article is for information purposes only and is not a substitute for therapy, legal advice, or other professional opinion. Never disregard such advice because of this article or anything else you have read from the Centre for Male Psychology. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of, or are endorsed by, The Centre for Male Psychology, and we cannot be held responsible for these views. Read our full disclaimer here.

Like our articles?

Click here to subscribe to our FREE newsletter and be first

to hear about news, events, and publications.

Have you got something to say?

Check out our submissions page to find out how to write for us.

.