The Case for Reintroduction of Colour Vision Screening at School Entry

Approximately 1 in12 males (8%) and 1 in 200 females (0.5%) in the UK inherit colour blindness. This means they can’t tell certain colours apart, so experience confusion in many areas of everyday life such as shopping, interacting with online information, looking at colour-coded charts, maps, sports team colours etc. As colour coding is so common in schools and the workplace, it is not surprising that colour blindness can impact educational attainment and limit career choices. For this reason in the UK colour vision screening was widely undertaken at school entry, that is until 2009 when it was discontinued, leaving approximately 450,000 schoolchildren every year – mostly boys - at a disadvantage educationally, with life-long consequences.

Screening for colour blindness is a quick, simple and inexpensive process, so what possible justification can be made for discontinuing screening for colour blindness? I will answer that question in a moment, but first let’s take a closer look at what colour blindness – correctly termed ‘colour vision deficiency’ (CVD) - actually is.

The most common types of colour blindness (‘red/green’) is are inherited via the X chromosome. Girls have two X chromosomes whilst boys have an XY pairing of chromosomes. The reason colour blindness impacts boys more is because boys only have one X-chromosome, and whereas a girl might have the colour blind defect on one X chromosome, this is usually compensated for by having no such defect on the other X chromosome (girls must inherit it on both X-chromosomes to be colour blind). Boys aren’t so lucky. Having only one X-chromosome they don’t have a backup, so just a single defect in their XY chromosome pairing means they will be colour blind.

“…screening for colour blindness could easily be undertaken by school nurses already visiting schools to assess pupils for other conditions. […] So why does colour vision screening at school entry no longer take place?”

The condition causes defects in the light sensitive cone cells in the retina of the eye. Red/green cone deficiencies are very common and often known collectively as ‘red/green colour blindness’. Colour blindness can vary in type and severity depending upon which type of cones are affected. People with colour blindness struggle to distinguish between many different colours. For example, someone with no red-detecting cones will be unable to perceive red in any colour, so purple will appear as dark blue, orange will appear as dark yellow and so on. This means many different colours can appear to be the same.

Figure 1. Comparison of what normal-sighted people see (left) to what colour blind people might see (right) in a science classroom.

In educational settings, colour blind students are at a disadvantage because they are unable to automatically distinguish information given in colour only. Educational resources – textbooks, worksheets, online resources, equipment, science experiments (see Figure 1), sport and so on - rely heavily on colour, so pupils with colour blindness are prevented from accessing information unless resources are properly adapted. However, screening for colour blindness could easily be undertaken by school nurses already visiting schools to assess pupils for other conditions. (See here for details). So why does colour vision screening at school entry no longer take place?

The current policy on colour vision screening in schools is the responsibility of the Department of Health which commissioned what is usually referred to as the Hall review (Hall & Hall, 2009), with the full title Healthy Child Programme, 5-9 Years: A Review of Evidence For (and Against) Health Promotion Interventions (Available from the HM Stationery Office). Page 10 of the Hall review states in the section on primary schools: “Colour vision screening should not be done”.

From what we know about colour blindness, why did the review come to this conclusion? The review, which was published in 2009, was crucially before:

· Software was available which allows people with ‘normal’ colour vision to view simulations of how colour blind pupils see their classrooms/resources etc

· Publication of both the Equality Act 2010 and the Children and Families Act 2014

· The Department for Education and the GEO recognised colour blindness could be considered a Special Educational Need and a disability

· The Department for Work and Pensions agreed the wording of the Equality Act 2010 Guidance Notes requires correction because it contains errors of fact in relation to interpretation of colour vision deficiencies.

Therefore, the Hall review of 2009 is out-of-date in relation to colour vision deficiency. Unfortunately, despite the Department of Education being made aware of this by Colour Blind Awareness and others, there has been no attempt by Government to rectify the situation.

Why might this be?

The Hall review discusses colour vision screening on page 40:

“13.5. We have found no evidence in support of screening for colour vision defects (40).

Somewhat surprisingly, several studies have found no evidence of educational

disadvantage due to impaired colour vision – though on occasion it may be wise to

check for this if it is suspected by parents or in the classroom.

13.5.1. There are many careers for which a colour vision impairment could be a

disadvantage or, in a few cases, a complete barrier. …Screening would be of no value to the young person unless they knew precisely what career they intended to pursue…. We do not think that this is likely to be worthwhile for all secondary school pupils.

This was a counter intuitive finding as some teachers believe it is important.

(40) Cumberland P, Rahi JS, Peckham CS. Impact of congenital colour vision defects on Occupation. Arch Dis Child 2005;90:906–908.”

At 13.5, the Hall review found it ‘somewhat surprising that there is no evidence of educational disadvantage due to impaired colour vision’ but only refers to one source at (40) above.

Despite the authors expressing surprise at the lack of evidence to support their prior assumption colour blindness must confer some educational disadvantage, they did not appear to take proper steps to investigate, relying upon a brief paper by Cumberland et al (2004).

It is important to note that the Cumberland paper describes a cohort study by Jefferis et al (2002) of school children born in 1958. Although being decades old doesn’t necessarily undermine a study’s findings, in this particular case, the age of the study is relevant because:

· In the 1960s and 1970s, schools used blackboards with white chalk, not red/green/black marker pens on interactive white boards.

· There were limited educational resources, mainly textbooks and blackboards. Textbooks used greyscale printing - meaning the vast majority of diagrams, graphs etc. would have been accessible to colour blind students.

· ‘O’/‘A’ Level exam papers were printed in black and white and relied upon hatching, shading, stippling etc. to differentiate information, not colour

· Career options available in 1974, when the average of the cohort left school were very different to those available to modern children. In 1974 there were no computers, barely any colour TV sets and there was no internet.

· Those schoolchildren in the Cumberland et al study had a colour blind diagnosis, so the schools were aware and the pupils could ask for help.

“You could argue that the conditions experienced by the 1958 cohort, cited in the Hall review, were much more helpful to colour blind children than those conditions experienced today, because by contrast, the modern classroom relies heavily upon the use of colour.”

You could argue that the conditions experienced by the 1958 cohort, cited in the Hall review, were much more helpful to colour blind children than those conditions experienced today, because by contrast, the modern classroom relies heavily upon the use of colour. Even today’s Early Years’ settings use tablets and apps, and none of this technology is designed from the outset to accommodate pupils with colour blindness. At the point of school entry and as current cohorts progress through school, their teachers rely on colour to make teaching points and upon software and other resources which are not regulated to ensure colour blind accessibility.

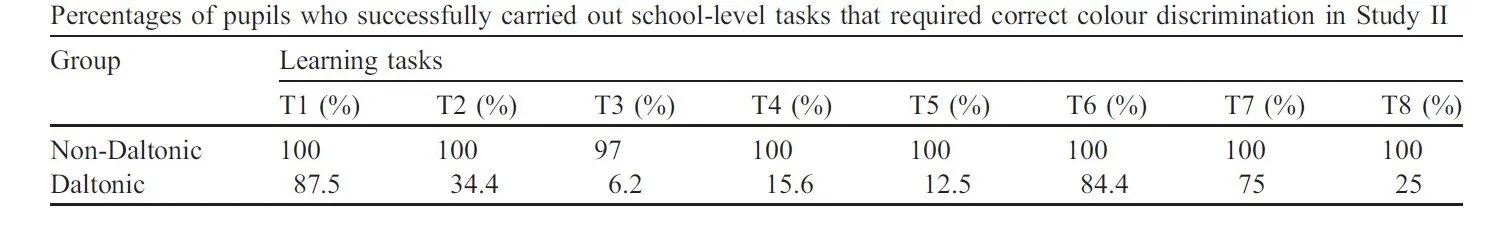

Sadly, even since 2009, little scientific research exists to test whether colour blind students are at a disadvantage in the classroom. It is readily apparent, to anyone with normal colour vision applying a modicum of common sense, that colour blindness must convey some educational disadvantage in the modern classroom. However one paper which did exist several years prior to the publication of the Hall review, Suero et al (2005) very clearly demonstrated that “Daltonic” children (those with some form of colour blindness) are at a definite disadvantage in some colour based tasks. The data in the image below (Table 1) shows, for example, that although children with normal vision scored 100 out of 100 on Task 5 (‘T5’), colour blind children scored 12.5 out of 100. On average across the 8 tasks, children with normal vision scored 99.6 out of 100 on tests that required colour vision, whereas colour blind children scored on average only 42.6 out of 100.

Table 1. Table of data from Suero et al (2005) showing scores on tasks that require colour in colour blind pupils (Daltonic) compared to those with normal vision (Non-Daltonic).

Another paper published several years before the Hall review (Cole, 2004) called ‘The Handicap of Abnormal Colour Vision’ states:

“All those with abnormal colour vision are at a disadvantage with comparative colour tasks that involve precise matching of colours or discrimination of fine colour differences …. The majority have problems when colour is used to code information, in man-made colour codes and in naturally occurring colour codes…. They can be denied the benefit of colour to mark out objects and organise complex visual displays. They may be unreliable when a colour name is used as an identifier. They are slower and less successful in search when colour is an attribute of the target object or is used to organise the visual display…”

Both the Suero et al (2005) and Cole (2004) papers demonstrate that Hall’s conclusions at the time of publication were incorrect. One other source quoted by Cumberland et al (2004) is the Health and Safety Executive’s guidance on colour vision.

This document states at clause 7: 'As colour deficient people can only see a limited number of colours, their ability to differentiate by colour is restricted. This means mistakes can be made in colour identification and colours can be confused.' Yet the Cumberland study only refers to this document as a reference for colour vision screening and diagnostic tests. It is therefore a mystery as to how Cumberland et al could possibly conclude that colour blindness should not be considered to create serious challenges in modern school settings.

The main contributor was Dr Janet Voke author of ‘Defective Colour Vision; Fundamentals, Diagnosis and Management’ (1986). I asked Dr Voke for her comments. On 24 October 2016 she stated:

“All colour vision defects can have a substantial effect on day-to-day activities and cause occupational consequences of error. It can affect and influence educational attainment, safety at work… career choice, ability to participate in sport on equal terms with others, ability to interpret colour information on charts or papers or computer displays...”

In …education there is a need for screening so that parents and pupils are aware of potential handicap. …the Equality Act 2010 should recognise this problem. In the past screening was done …A review of this situation is, in my opinion, long overdue since most optometrists do not include colour vision screening in their range of tests as they are not obliged ...by law.”

Dr Voke’s words echo the findings of a survey published in 2017, showing that colour blind people are significantly more likely than normal-sighted people to experience reduced quality of life for health, emotions, and especially in careers.

Further, Hall’s conclusion that secondary school students are unlikely to benefit from screening is bizarre. With proper support colour blind students will have a better understanding of teaching points which will improve their learning and educational achievements. Diagnosis will also enable these students to gain access to Access Arrangements for external exams to which they are entitled but where undiagnosed, unable to access. Consequently, their life chances could be improved by screening, as could their further education/career choices.

Unfortunately, the Hall review conclusions have been widely adopted across government and perpetuate discrimination against colour blind pupils. This can be seen in a series of Ministerial letters from across government, including Equalities (Dinenage, Ref GEO2016-0054777) and Communities and Social Care (Burt 10/06/15 Ref PO00000935362). Both quote the Hall review verbatim: “Testing for colour blindness in children is not routinely undertaken in England as research has shown that, nationally, colour vision defects confer no functional disadvantages in relation to educational attainment or unintentional injury”.

“…it is extremely concerning that one flawed review can have such an impact on such a huge number of children, and highlights the serious need for governments to address how expert reviews can be better vetted in future.”

A Freedom of Information request (response FOI 1063595) to a letter seeking confirmation of the source of the ‘study’ quoted in Dinenage GEO-2016-0004795 confirms the source of the ‘research’ to be the flawed Cumberland et al paper citing the study of the cohort born in 1958.

It does not help that colour blindness falls across three Government Departments – Health, Education and Equalities – resulting in a lack of joined-up thinking and no single Department willing to take responsibility to fix the problem. Nonetheless it is extremely concerning that one flawed review can have such an impact on such a huge number of children, and highlights the serious need for governments to address how expert reviews can be better vetted in future. In this case, for example, why did no-one speak to Dr Voke at least? One might be cynical in thinking this could have been because the Department was looking for excuses to save money and it was convenient not to properly investigate.

Where do we go from here?

As a direct consequence of the Hall review, awareness of colour blindness has been minimised for parents, teachers and optometrists.

I am all too aware of the issue of lack of parental awareness because I was one of these parents and only discovered by chance that my son has colour blindness. Like most parents I wrongly assumed that my children would have been screened at school entry (as I was) and by our optometrist. Also, I doubt most parents are aware that screening for colour blindness does not currently form part of the NHS eye test for children in England and Wales. It was a shock to me to discover that, at present, screening is at the optometrist’s discretion. In many cases parents have to specifically ask for it.

Teacher training and awareness in schools needs to be revived, including amongst Special Educational Needs Co-ordinators, of the indicators and positive interventions.

Children with colour blindness have a basic human right not to be discriminated against on the grounds of disability, nor – with colour blindness being 16 times more common in boys than girls - be subjected to indirect sexual discrimination. These rights are supposedly protected under the Equality Act 2010 plus the Children and Families Act 2016 places an anticipatory obligation on schools to ensure schoolchildren will not be discriminated against.

Resources and teaching methods can be easily and inexpensively modified for the colour blind child, meaning that low self-esteem issues, negative labelling and lower attainment arising from lack of detection and support can easily be minimised. Maintaining the status quo is not an option. It is essential the UK Government addresses the lack of support for pupils with colour blindness as a matter of urgency, otherwise colour blind pupils will continue to be at a disadvantage and victims of (often) inadvertent discrimination by schools, teachers and potential employers. Colour vision screening at school entry must be re-introduced as soon as possible.

Scroll down to join the discussion

Disclaimer: This article is for information purposes only and is not a substitute for therapy, legal advice, or other professional opinion. Never disregard such advice because of this article or anything else you have read from the Centre for Male Psychology. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of, or are endorsed by, The Centre for Male Psychology, and we cannot be held responsible for these views. Read our full disclaimer here.

Like our articles?

Click here to subscribe to our FREE newsletter and be first

to hear about news, events, and publications.

Have you got something to say?

Check out our submissions page to find out how to write for us.

.