Misandry, identity politics, and DEI: An interview with Dr Paul Nathanson

What do you call someone who specializes in female reproductive health? That’s right – a gynecologist. But what do you call someone who specializes in men’s reproductive health? An andrologist. That’s a much less familiar term, but why? Prostate cancer kills as many men as breast cancer kills women. Similarly, you may be wondering what ‘misandry’ is. A simple explanation is that misandry is to men as misogyny is to women. Arguably, misandry (pronounced misandry in the UK and misandry in the US and Canada) impacts men these days just as much as misogyny impacts women, but it remains controversial to say so despite the publication of four rigorously academic books on the subject, co-authored by Dr Paul Nathanson and Dr. Katherine K. Young.

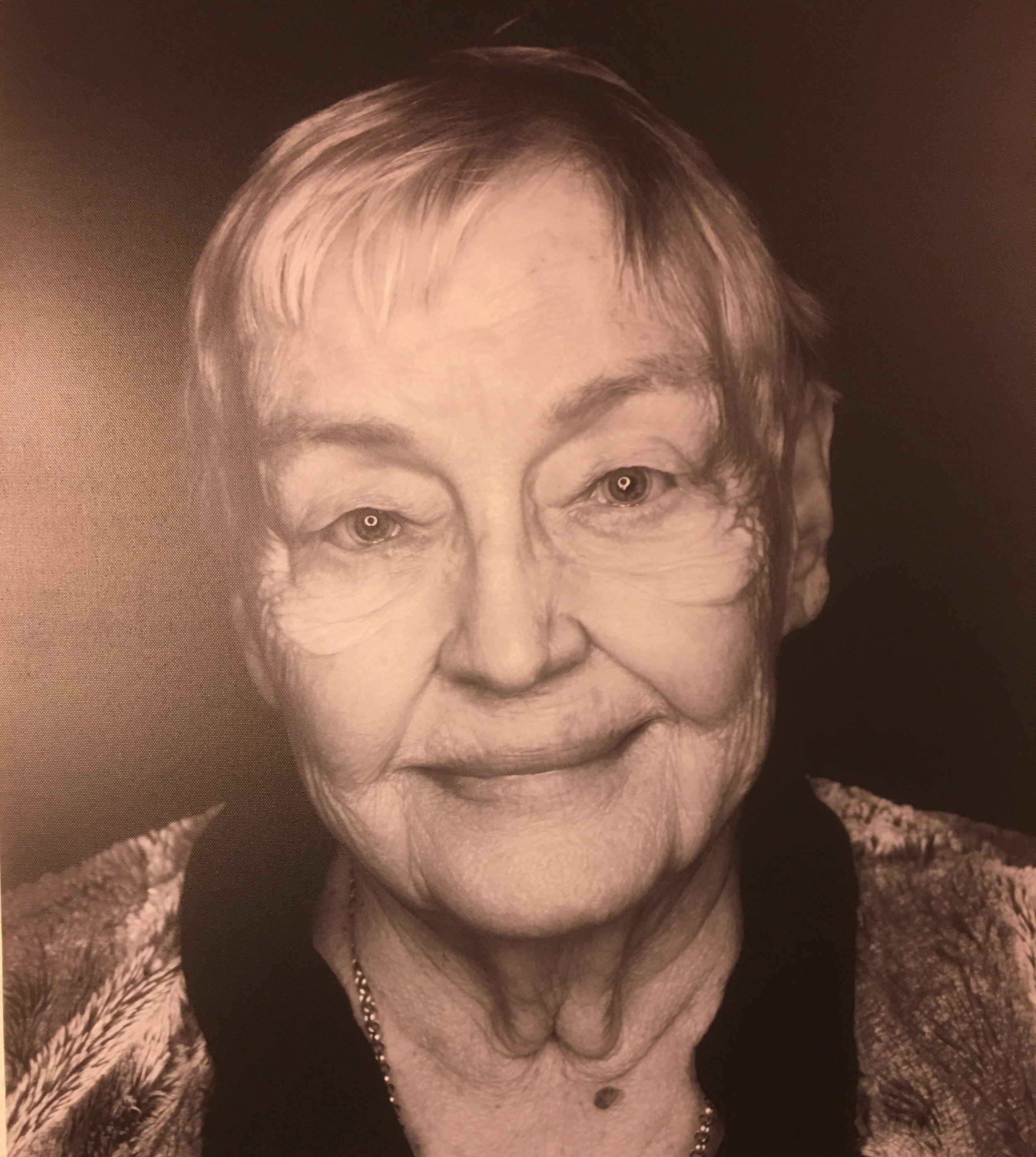

John Barry (JB): Paul, thank you for agreeing to be interviewed. Readers of Male Psychology might know you best from your ground-breaking series of books on misandry: Spreading Misandry: The Teaching of Contempt for Men in Popular Culture 2001), Legalizing Misandry:(2006), Sanctifying Misandry (2010), and Replacing Misandry (2015). At a time when it could be career suicide to challenge the focus on female victimhood, it was outstanding that your books were describing how men have become seriously exposed to misandry in Western culture. Let’s start the interview by finding out about the background to those books. What were the circumstances that brought the books into being?

Paul Nathanson (PN): Each of us had a distinctive research background. Both of us are in the field of comparative religion (a.k.a. religious studies). Katherine Young’s area of specialization is Hinduism. Much of her research involves analyses of Sanskrit and other traditional literary sources. But some of her research involves the application of anthropological methods to learn how traditional Hindu attitudes toward caste and women had been affected by the various forces of modernity. When I became her doctoral student, however, she was already saying that it wasn’t enough to study changing attitudes toward Hindu women, because the same forces were changing attitudes toward Hindu men as well. In other words, you couldn’t learn much about women without also learning about men. What we needed, therefore, was a “stereophonic” or “stereoscopic” method. Consequently, she was interested in the questions that I was asking about men.

My area of specialization is Western religion. More specifically, I’m interested in the surprisingly blurry relation between Western religions and secularity. At first, I studied that in the context of popular culture, which, though secular on the surface, remained deeply embedded in the cultural matrix of the Judeo-Christian tradition. My dissertation (and first book), for example, was on The Wizard of Oz as a “secular myth” of America. In it, I rejected the common definition of myth (a synonym for “lie,“ “primitive belief” or childish error”) in favor of an anthropological one: a symbolic story about origin and destiny, one that can be understood at personal, communal or cosmic levels .Given her expertise in myth, Katherine became my dissertation advisor. At the core of my research was a dense tapestry of stories about the way things were in the beginning (a paradisal garden, beyond time and space, as our primeval home), the way things are now (everyday life within time and space, or history) and how things will be once again (return to paradise as our eschatological home). Moreover, I found that the secular myths of our time, such as classic movies, do for our society much (but not quite all) of what traditional myths do for religious societies. In short, secular religions - including secular myths and the secular rituals that accompany them - provide communities with cultural venues for the creation of order and meaning, without which no enduring community would be possible.

But I soon realized that popular entertainment was only one venue of secular religion in general and secular myth in particular. That brought me to the study of political ideologies as secular religions. In the 1970s and 1980s, a major narrative genre in popular culture, mainly in movies and televisions shows, assumed a worldview that was gynocentric or even misandric. This is when Katherine and I began our collaboration on the study of feminism as a secular religion and began referring to ideological feminism (as distinct from egalitarian feminism) as a specific form of religion: fundamentalism. Much more recently, I’ve expanded my scope by placing ideological feminism in the larger context of closely related, and closely allied, ideologies.

“One post-biblical interpretation of that story, however, placed heavier blame on Eve […] than on Adam […]. This is precisely what feminist ideology reverses, placing the blame on men instead of women. This makes Original Sin synonymous with the rise of “patriarchy.” The feminist story […] like the biblical one, will ultimately end with a return to paradise - a feminist utopia”.

JB: You and Young are academics specializing in studying religion, but only one of your misandry books was about religion. How new was the topic of misandry to you both, and how did your religious studies backgrounds influence your approach to the subject?

PN: It’s true, John, that only Sanctifying Misandry is specifically about traditional forms of organized religion, beginning with feminist theories about a primeval goddess religion (the conspiracy theory of history) and modern attempts to restore goddess religion either within established churches or beyond them. Because the basic paradigm of feminist ideology relies heavily on the Christian doctrine of Original Sin, but in reverse, we decided to devote one volume to that topic. In the biblical tradition, Adam and Eve live in the eternal peace and harmony of Eden. Both succumb to temptation. Both fall from grace. Both are punished by, apart from anything else, exile from paradisal eternity into history. This leaves them and their descendants in the chaotic world that we know in everyday life. The scriptural story ends ultimately, however, with their remote descendants returning to paradise either after death or after the end of history (a.k.a. The Kingdom of God, the Heavenly Jerusalem, the Messianic Era and so on). One post-biblical interpretation of that story, however, placed heavier blame on Eve (and her female descendants) than on Adam (and his male descendants). This is precisely what feminist ideology reverses, placing the blame on men instead of women. This makes Original Sin synonymous with the rise of “patriarchy.” The feminist story begins in a primeval paradise, an egalitarian one (according to some variants under the aegis of a Great Goddess). Then, something goes wrong. Either local men rebel (inexplicably) against the egalitarian paradise (and its Goddess) or brutal societies invade (and replace the Goddess with their own gods and goddesses). Either way, men establish a patriarchal society. This original sin leads to countless centuries in which men oppress women. The story, like the biblical one, will ultimately end with a return to paradise - a feminist utopia (or feminist paradise under the renewed aegis of a Great Goddess).

But the other volumes, too, are about religion, albeit in the more generic sense of political ideologies as implicit or secular religions (of a particular kind). The focus in those volumes is not on misandric mythology but on its misandric fallout in everyday life: law, journalism, family life, politics, entertainment and so on.

Misandry was not a new topic to me, because I had noticed it even as a young child on the path to becoming gay (without naming it, of course, let alone understanding it). I was a classic victim of bullies, both male bullies and female ones. Although I never thought that I was anything but a boy, I did find some prevalent notions of masculinity alienating and threatening. In college and then in grad school, though, I thought in much more detail about misandry.

By this time, the Vietnam War was raging, which added intense anxiety to my confusion about, well, everything. I was living in New York, supposedly doing graduate research at Columbia University, but everyone else was ranting on campus and in the streets about doves and hawks. I had no interest in the political aviary and even less in Geneva Conventions. I tried to learn something about the war by reading Ramparts from cover to cover every month, although I quickly drew the line at sit-ins and teach-ins. But I learned nothing about what was really troubling me. Even though I agreed with the protesters in denouncing the war, I couldn’t stand being in the same room with them. For one thing, I reacted against the smugness and self-righteous that we now call “virtue signaling.”

But my problem was deeper than that. As usual, throughout my life, it was about personal identity. It was no longer my identity as a gay man that troubled me. Rather, it was my identity as a man, period. In other words, it was about not only masculinity but also maleness. I couldn’t see any link in myself, at any rate, between either masculinity or maleness and war. From the beginning, that has been at the very heart of my research on men, masculinity and maleness (apart from misandry). One chapter in Replacing Misandry sums up my theory.

I found the military draft very threatening not only on personal and legal grounds but also on moral grounds. I was ready to talk about that, barely, but no one else was. Some feminists joined anti-draft rallies. They carried signs that read “Women say yes to men who say no.” But even they didn’t ask why “universal conscription” was for men but not women. As for men, it was okay in the late 1960s to rebel against this or that war on political grounds (as it had not been in earlier wars), even to oppose the racially unfair draft on political grounds, but not to do so in any way that might suggest personal vulnerability, let alone cowardice. That was going too far even for men who were ready to trash every other “traditional” notion - from style (in clothing, say, or music) to religion (none) to adulthood itself (earning money, marriage and fatherhood) as “bourgeois.” They did have a worldview, but it wasn’t even remotely like my own. It was hedonism, a search for oblivion through sex and drugs.

“I recognized the paradigm of ideological feminism in other historical episodes of mass hatred such as theological anti-Judaism […] This is not to say that feminists want to indulge in mass murder, however, because they […] understood that, in democracies, they can achieve their political goals much more easily and effectively by resorting to legislation.”

In 1969, I returned home to Montreal. Defeated, I turned once again to feminism. If women could question the meaning of femininity, after all, why could men not question that of masculinity? If women were disadvantaged in various ways, what about the ways in which men were disadvantaged? But after a few years of reading feminist literature as an adult, I began to realize that feminism was not merely gynocentric, which I found disturbing enough, but misandric. It no longer had anything to do with sexual equality. Instead, it had turned into a dualistic ideology. Increasingly, feminists blamed all evil and suffering on “them,” on “patriarchy” and therefore on men as a class. At that very moment, people were rejecting the Civil Rights movement of Martin Luther King in favor of the Black Power movement. In both cases, this was the culturally propagated and institutionalized expression not of indifference to the “others” but of hatred toward them. And I define “hatred” not as a personal and transient emotion (although it can look like anger) but a collective urge to harm some target group (or more than one) as an end in itself. This was not justice but revenge.

My main point here, though, is that I recognized the paradigm of ideological feminism in other historical episodes of mass hatred such as theological anti-Judaism, which eventually morphed into racial anti-Semitism and most recently into political anti-Zionism. And those, in turn, are variants of anti-Westernism (a.k.a. wokism). This is not to say that feminists want to indulge in mass murder, however, because they and their ideological allies have long understood that, in democracies, they can achieve their political goals much more easily and effectively by resorting to legislation than by resorting to violence in the streets.

JB: Your misandry books are legendary for many people. For example, in an interview in Male Psychology last year, Professor Miles Groth commented that your books were “spot on”. Similarly, in the first British Psychological Society (BPS) textbook on male psychology, Perspectives in Male Psychology, we cited your first two misandry books, because they are the most thorough evidence of negative depictions of men in the media. Given that misandry is a topic most people have never heard of, and a phenomenon that many of your peers in the humanities and social sciences would not recognize, were you surprised at the impact your books have had?

PN: We were surprised, to say the least, and recognized in the late 1990s that we would require relentless documentation of this phenomenon. If we didn’t do that, who would? Otherwise, no one would take a counter-intuitive argument seriously. We originally intended to write one introductory chapter on evidence of misandry in popular culture. But the evidence was (and still is) overwhelming, so that chapter quickly turned into the first of four volumes on misandry not only in the popular culture of movies and TV shows but also in the elite culture of academic treatises, political ranting and legal codes.

The word “misandry” is by now, thanks to digital technologies, recognizable to far more people than it was a few decades ago. But I suspect that this is still true more often for men than for women, because feminism has long provided women not only with their own vocabulary (words that have become clichés at best and slogans at worst) along with their own verbal strategies (such as linguistic inflation and linguistic deflation).

JB: Skipping forward a few years, your most recent article, “DEI Must Die: Hatred as a Contagion,” will no doubt be considered controversial by some people. But first, what is DEI? In the UK, gender equality schemes like Athena Swan started out as a way to promote the careers of women in the fields of science, technology and engineering (‘STE’), but this was extended to mathematics (‘STEM’), then medicine (‘STEMM’), and eventually all of academia, including the humanities, social sciences, business and law. The same thinking around gender equality - that unequal representation is unfair - has now been extended to race, disability and sexuality. Is DEI a straightforward extension of misandry and patriarchy theory, two of the themes described in your misandry books?

PN: DEI refers to policies that require racial, sexual or gendered “diversity, equity and inclusion.” It does not, however, include intellectual diversity, equity or inclusion. Some points of view are beyond the pale - including those that that rely not only on religion or conservatism but also those that rely on science or even common sense. The problem is precisely this contradiction (which I attribute to dishonesty, not merely to stupidity). Just as some people are innate victims (by race, sex or gender) and thus deserving of government remediation, other people are innate oppressors (by race, sex or gender) and thus undeserving. (Unlike traditional Western religious, moreover, this secular one offers members of oppressor classes no possibility of redemption. And how could it be otherwise? Guilt is the result of innate or ontological status, from this perspective, not of freely choosing between moral and immoral alternatives.)

Apart from the profound moral problem of this political strategy, institutionalized discrimination, are some obvious practical ones. This makes earning personal merit not only unimportant, for example, but also undesirable. And the results of that in both education and employment are catastrophic. Justices of the American Supreme Court now acknowledge, after decades of conflict, that the Constitution prohibits this kind of discrimination. (And it is discrimination per se, by the way, not merely “reverse discrimination.”) But the struggle against this policy continues in Canada and many other Western countries (and even in the United States as institutions try relentlessly to find legal loopholes). On both moral and practical grounds, therefore, I argue that DEI must “die.”

“Diversity is a universal and self-evident fact of life. But it’s not an end in itself and is neither inherently good nor inherently bad. […] the world would be intolerably boring if everyone were the same.) Too much diversity, however, entails conflict and ultimately fragmentation.”

DEI is not a “straightforward extension of misandry,” because it’s not straightforward about anything. It relies on ideological jargon and linguistic trickery instead of reason or evidence. Not everyone knows what the word “equity” actually means, for example, assuming that it means “equality.” It does not. Equality has a long history of referring to equality of opportunity. Equity, by contrast, now refers in political discourse (unlike economic discourse, where it originated) to equality of result. The assumption (unsupported by evidence) is that any disparity of result by class - that is, by race, sex or gender - can be explained only as the result of “systemic racism” (or other forms of prejudice) on the institutional level or of “implicit bias” on the personal level. (Denying the latter is, not surprisingly, taken as obvious evidence of it). Because both forms of prejudice are inherently evil, advocates of DEI declare, the state must prevent them by establishing quotas or other forms of “affirmative action” to “level the playing field.” These are punitive measures, of course, because they achieve their goals for some people (presumably innocent victims of oppression) by punishing other people (presumably guilty oppressors). To explain that, advocates of DEI must resort to the morally dubious notion of “collective guilt” (which has a long and lamentable history of its own). In other words, they claim, some people are guilty by virtue of birth, not by the choices that they actually make as moral agents.

In the case of sexual and gendered prejudice, plenty of evidence indicates that men are statistically disadvantaged in some ways and that women are statistically privileged in other ways. This evidence comes from many fields, including law (much heavier sentences for men than for women convicted of the same crimes), education (much higher rates of men than for women who drop out of high school or college - or don’t go on to college at all), employment (the rise of an unemployable male underclass) and so on. But no advocate of DEI ever finds it necessary to remediate their disadvantages (let alone to declare that they must be the victims of “systemic discrimination” or “implicit bias”).

JB: Are there any positive aspects of DEI, such as raising awareness of inequalities, highlighting benefits of including the perspectives of people from diverse backgrounds? What are the least positive aspects, such as biological men in women’s sports, anti-white sentiment, creating a culture of low expectations which places demographics before ability?

PN: In theory, diversity and inclusion (but not equity) can be either good policies or bad ones. As politically correct slogans, however, they obscure more than they reveal by overlooking important distinctions, even paradoxes, in the context of identity politics

Diversity is a universal and self-evident fact of life. But it’s not an end in itself and is neither inherently good nor inherently bad. I’ll refer here to diversity in connection only with human communities, not with nature in general). Enough diversity presents any population with a wide range of possible resources (genetic, physical, material, intellectual, spiritual and so on), and therefore increases the likelihood of cultural enrichment and even communal survival. (Moreover, the world would be intolerably boring if everyone were the same.) Too much diversity, however, entails conflict and ultimately fragmentation. No community can endure for long unless members, both as individuals and as groups, are united in their loyalty to something larger than themselves. Otherwise, why would they contribute and sometimes sacrifice for the common good? Citizens vote in their own self-interest, to be sure, but should they always do so? Is a democratic society nothing more than a collection of self-interested citizens or identity groups? Is there nothing admirable about voting for the common good (society as a whole) in some circumstances? Everyone knows that modern democracies amount to more than elections and vote counting. One explicit goal of any modern democracy is to prevent the tyranny of a homogeneous majority. But what happens when minorities ally themselves to create a heterogeneous majority? Why would that form of tyranny be preferable to the other?

I’d say something similar for inclusion. Forming a healthy identity, whether as an individual or as a group, entails a strong sense of being like others (and therefore worthy of inclusion among them) but also a strong sense of being unlike others (and therefore of distinctive or unique value). I think that this paradox is a fundamental and universal feature of the human condition.

So, yes, cultivating diversity and inclusion can be desirable. Doing so is morally legitimate, therefore, unless it involves coercion by institutions or by the state. But coercion is precisely, by definition, what DEI policies do.

Equity is another matter entirely. As I say, it presupposes not equality of opportunity but equality of result. Ironically, this contradicts the notion of diversity by assuming that all people are interchangeable - which is to say, that they all have the same aptitudes, skills, priorities or interests - and therefore that they would all reap the same rewards for their efforts in any endeavor were it not for externally imposed barriers such as “systemic racism.” But that assumption is false. It relies on utopianism (a characteristic feature of all ideologies) instead of pragmatism, let alone compassion.

“To be blunt, the bullies ultimately unwittingly empowered me. I often wonder what would have happened if my parents (whom I never told) or teachers had intervened to protect me. But I think now that I had to learn self-reliance for myself.”

The problems of DEI are inherent; no reform can mitigate its moral and intellectual bankruptcy. Some problems are obvious. Affirmative action aims to help some people by punishing other people, for example, the latter being personally innocent but collectively guilty by virtue of innate racial, sexual or gendered identity. Consider that in the context of transgender policies. Allowing boys or men on athletic terms of girls or women, even men in women’s prisons, supposedly promotes diversity and inclusion but actually enforces the ideology of one group at the cost of depriving or endangering another - that is, women.

At a deeper level, though, DEI is symptomatic of the broader attempt to replace personal merit with collective identity in recruitment. But lowering academic or other standards for political reasons ultimately presents the threat of incompetence to society as a whole. (How many people want physicians who might have received their credentials due to race, for example, instead of intelligence and hard work?)

And at a still deeper level, DEI is symptomatic of a profoundly anti-intellectual crusade, one that originated decades ago with the rise of postmodernism and has led since then inexorably toward the repudiation not only of objective truth (or at least the search for it) but of reason itself - including science.

JB: One issue that I think is underappreciated is giving people the identity of ‘victim’. True, in one sense they are ‘empowered’ by legislation, but on a deeper level they can be undermined. According to one study, people can now be fooled into thinking that they are experiencing ‘microaggressions’. It’s hard to imagine that as being empowering. What are your thoughts on this?

PN: I know from my own “lived experience” (as if there could be any other kind of experience) about the harm that words can do. In my case, bullying took the verbal form of “microaggressions.” (Physical assault would have been another matter entirely.) But I grew up and got over the bullies at school. Scar tissue remains as my general lack of self-confidence, it’s true, but that no longer leaves me paralyzed. I no longer run home in tears or call a psychotherapist when someone ridicules me, let alone when someone disagrees with me. To be blunt, the bullies unwittingly but ultimately empowered me. I often wonder what would have happened if my parents (whom I never told) or teachers had intervened to protect me. But I think now that I had to learn self-reliance for myself. (This is what Dorothy learns in The Wizard of Oz, which was one reason for my writing a book about that movie.) Growing up is more difficult for some children than for others, it’s true, but growing up means nothing if not learning to think for ourselves and take responsibility for defending ourselves in the public square. The world is not always comfortable, let alone reassuring, but we must still learn by experience how to live in it. And if that means hearing - or saying - unpopular things, then so be it.

JB: You start “DEI Must Die” by saying that people and societies need healthy identities: “To attain a healthy identity, every person and every community must be able to make at least one contribution to the larger world (family, community or society) that is (a) distinctive; (b) necessary to society; and (c) publicly valued.” Do you think that young men these days turn against society because they don’t believe that they can make a positive contribution in any of these three ways?

PN: Well, that’s one reason, not necessarily a conscious one. Countless factors influence everyone’s life. I’m thinking primarily about men as a group, or class, not as individuals (although personal identity and group identity are obviously linked). I’m interested in cultural patterns, at any rate, not personal anomalies or idiosyncrasies.

By the way, John, your question could be turned around. Do men who can’t make distinctive contributions reject society? Or does society reject men who can’t make distinctive contributions? The answer is often “yes” to both questions. In a world that remains indifferent to boys and men at best and hostile to them at worst, a world that therefore has no place for them as such, why should anyone be surprised to find increasing numbers of men on the outskirts of society (as uneducated, unemployed, unmarried, unaffiliated with any community), outside of society (as addicts or criminals) or outside of life itself (as suicides)?

But as Katherine and I say in Replacing Misandry, this problem did not originate with feminism or even with modernity. It emerged gradually over the past ten or twelve thousand years - beginning in the late Neolithic period - due to a series of technological and cultural revolutions such as the Agricultural Revolution and the Industrial Revolution. These affected the ways in which men (and women) perceived the male body and its value to the community.

JB: Regarding fatherhood you wrote: “Unlike mothers, fathers don’t necessarily provide their children with unconditional love, although many do, but do provide them with earned respect.” The idea that men and women are different is unfashionable in the social sciences, so some people will find this concept unfamiliar. Can you explain it a little please?

PN: I think that psychologists have reached the end of the road with the paradigm of “social constructionism.” Were it not for cultural interpretations of nature, according to this doctrine, men and women would be interchangeable except for the seemingly trivial ability of women to gestate and lactate. That cultural reductionism is no longer tenable (although I’d say the same thing about biological reductionism). Men and women are clearly different in many (though not all) ways. And some of these ways are clearly innate, not learned. Both mothers and fathers have distinctive functions within family life that. Both are necessary. And both should be publicly valued. The result is complementarity. For obvious reasons, mothers are emotionally more closely bound than fathers to infants and young children. What infants and young children need most to know is that they can expect unconditional love within the home - usually (though not necessarily) from their mothers. Older children, however, must prepare to leave home and enter the larger world. What they need most to learn is how they can earn the respect of others - first their fathers, then their relatives, their friends, their classmates, their colleagues at work and so on. The message from mothers is ideally, “I’ll always love you no matter what you do or don’t do.” The message from fathers is ideally, “I’ll respect you if you behave honorably.” Fathers can love their children and usually do, but that’s not their primary and necessary function. In any case, respect is a form of love unless you assume - and I don’t - that love is always synonymous with emotion. In biblical texts, various Hebrew and Greek or Latin words are sometimes translated inaccurately into English as “love.” Most of them refer to acts of will (self-sacrifice) and are therefore moral commandments, not emotions.

I’ve described a general pattern. Real life, of course, can be more complicated than any pattern. Due to death, divorce or abandonment, after all, some children have always been left without one parent or both parents. Every community finds ways to help children in need, often by appealing to altruism. But these circumstances have always been exceptional, not normative - and certainly not ideal. Not until the rise of no-fault divorce, that is, and of “alternative families.” But I argue here, on historical and cross-cultural grounds, only that the distinction between unconditional love and earned respect is probably universal. It might or might not matter which parent provides which, but it would matter a great deal if one parent were in the position of trying to provide both. That would give children a classic and confusing “double message.”

“yes, there’s always “still a long way to go.” How could it be otherwise for any ideology that promises utopia […] Ideologues must convince followers that they have already succeeded heroically in paving the way for utopia - but also that they nonetheless remain oppressed victims. The revolutionary struggle is never over and will always need fresh recruits”

JB: Andrew Breitbart’s book has a characteristically entertaining chapter describing how social scientists such as Theodor Adorno, in the US as refugees from Nazi persecution, were very cynical about the American dream and went about the happy environment of free and sunny Los Angeles dressed for a Frankfurt winter and being thoroughly miserable. However, Adorno and others of the Frankfurt School were instrumental in the “the long march through the institutions” of cultural Marxism. In your opinion, is the current wave of DEI the final step of this march, or is there - as you keep hearing from feminists - ‘still a long way to go’?

PN: Well, the final step for any utopian ideology is the annihilation of one civilization, root and branch, so that a new one can rise from the ashes and over the ruins. One implication is that those who don’t support the revolution - and I do mean revolution as distinct from reform - are not merely lazy or stupid but evil. In other words, they are either heretics or infidels and must be eliminated in one way or another. The end, presumably, justifies the means.

The recent rush to replace personal merit with collective identity, as DEI does, is surely a disturbing harbinger of things to come. But the mere fact that it still relies on euphemisms in public discourse indicates to me that its advocates are aware of having not yet completed their cultural revolution. So yes, there’s always “still a long way to go.” How could it be otherwise for any ideology that promises utopia (a perfect world that, unlike paradise, will be built within history)? Ideologues must convince followers that they have already succeeded heroically in paving the way for utopia - but also that they nonetheless remain oppressed victims and must therefore continue to fight. The revolutionary struggle is never over and will always need fresh recruits, because achieving perfection (utopia) is a fantasy in this finite world. Otherwise, why would anyone carry on the struggle?

Your question is really about a form of “cognitive dissonance,” painful recognition (in this case) of a huge gulf between the way that things are and the way that things should be. And one way of coping with distress of this kind is to create defense mechanisms such as avoidance or denial. In 2024, millions of Americans were shocked to find that millions of other Americans were at last pushing back against a glaringly obsolete Democratic platform. Voters had many reasons for rejecting the Democrats, but one of them was surely that party’s lurch, within one or two generations, from liberalism to progressivism and most recently to wokism. Most American voters said “no” to the Democrats. But will leaders of the party listen to them? Or will they bring the same ideology to equally polarizing elections of the future? So far - only two weeks have passed since the election - many Democratic leaders prefer to blame their failure on strategic errors such as failing to “communicate the message” clearly enough. Others condescendingly blame voters themselves for being too stupid, too racist or too sexist to know what’s good for the country or even for themselves. I doubt that any electoral failure can change the fundamentalism of true believers, who will therefore succumb for years or decades to “cognitive dissonance.”

JB: You describe the dualistic structure of woke thinking, with the “us” versus “them” and victim versus oppressor. This is very much in line with social identity theory, which predicts that people form in-groups and out-groups extremely easily. However it is less well known that the identity of being male is the one identity that doesn’t create an in-group, putting men exceptionally at risk of attack by people holding other group identities. Do you think there is a case to be made for men to join in the “competitive suffering among those who claim to be oppressed”?

PN: My answer is long and complicated, John, so bear with me. First, I’m not so sure about men being either unable or unwilling to see themselves as an “in-group.” Not being a social scientist, however, I don’t know precisely how specialists use that expression. Both historically and cross-culturally, at any rate, men have indeed understood what binds them together. Every society, until our own right now, has clearly differentiated between the spheres of men and women: formally or informally, explicitly or implicitly, strictly or flexibly. Every society has had a gender system, in other words, no matter how rudimentary. It you can say that men as such belong within a class, then you can say that they belong to an in-group - but also, of course, to many other in-groups. I suspect that your question refers to something else, however, so I’ll respond in connection with the current (and highly unusual) context.

Today, most people around here deny the need for, let alone the legitimacy of, any gender distinctions at all. Some people deny even the existence of sex differences. Both denials amount to an unprecedented cultural experiment, which originated with the rise of egalitarian feminism sixty years ago. Egalitarian feminists, at least American ones, have tended to believe that men and women should be not merely “equal” under the law but also identical for all purposes except for motherhood (but not fatherhood) and perhaps military service. So entrenched has this understanding of equality become - egalitarianism, after all, is the conventional wisdom and lingua franca of all democratic societies - that most people, both women and men, have either eagerly or grudgingly accepted it at face value. (But remember that ideological feminists have adopted a very different point of view: emphasizing the innate differences between men and women on the assumption that these differences add up to the innate superiority of women over men.)

The initial result of egalitarian feminism was pervasive gynocentrism, because only women demanded changes to bring about sexual equality. Their worldview, by definition, revolved around the distinctive needs and problems of girls and women, assuming that boys and men have none and are therefore of no interest to reformers. From the beginning of their second-wave, feminists focused attention exclusively on the ways in which women lacked equality with men, ignoring the ways in which men lacked equality with women. (Many people still refer foolishly to “women’s equality,” forgetting that there can be no such thing as equality without being equal to something else.) These feminist pioneers could do so almost immediately, moreover, because no more young men were drafted for military service after 1973, although young men alone have been required to register for it since 1980. And the possibility of a renewed draft, either for young men alone or for young men and young women, is already looming as a major controversy.

“men are at last waking up to what every other group has recognized. Once group identity defines public discourse, no group, can afford to ignore it. Any group that does is doomed to increasing marginalization or even persecution.”

For a few decades, at any rate, egalitarian feminism worked very well for working women. They relied on institutionalized sexual equality to provide women with access not only to the same jobs as men but also to equal pay for equal work (or “equal pay for work of equal value,” which is not the same thing). Even so, women demanded and quickly attained adjustments to suit the needs of working mothers and to protect women from very broadly defined “hostile workplaces” or “sexual harassment.” Whether men liked these adjustments or not, most recognized the moral legitimacy of sexual equality per se, and few tried to argue against that. Those who did, even by taking equality seriously from the perspectives of both women and men, were silenced in one way or another as “sexists” or “misogynists.”

Ideological feminism went beyond gynocentrism to outright misandry. This movement was - and is - about female superiority, not sexual equality. And by 2010 it was leaving the supposedly isolated academic realm to enter the public square as a new orthodoxy. Graduates from departments of women’s studies prevailed in the new generation of teachers, lawyers, journalists, politicians and legislators. Several years ago, ideological feminism was incorporated, along with other identitarian movements, into an alliance that opponents call “identity politics” or “wokism” (although one of those movements, transgenderism, has entered into direct conflict with feminism).

I won’t re-tell the stories of either egalitarian or ideological feminism, which Katherine and I discuss at great length in the four volumes of our misandry series. It’s enough to add here that although women have been arguing for decades about the helpful and unhelpful effects of feminism on women, a few of them - beginning thirty years ago with Christina Hoff Sommers almost alone and continuing now with Janice Fiamengo and more than a few other women - have taken the risk of arguing that feminism has had disastrous effects on boys and men. But here’s my point in response to your question. More and more men are doing the same thing on their own behalf.

When Katherine and I began our research on misandry, hardly anyone even bothered to review our books. (Only the first volume got some attention on talk shows because of its focus on “sexy” popular culture; not all of our interviewers had bothered even to read more than the first chapter.) Now, thanks to the internet and some degree of courage in the face of implacable hostility toward the “manosphere,” word is out. It’s no longer true that men, as a class, are afraid to identify and argue against those who try to silence, ridicule or shame them into compliance with various woke ideologies. More than a few people - black and white, male and female - reacted angrily when President Obama tried to shame black men (and implicitly all men) who failed to support the presidential campaign of a black woman. He could think of no explanation other than misogyny. Remarks of this kind - there were many - might well have influenced the election. In any case, men are at last waking up to what every other group has recognized. Once any group throws down the gauntlet by defining public discourse in terms of identity, no group, can afford to ignore it. Any group that does so would be doomed to increasing marginalization or even persecution. And that, as everyone knows, leads almost inevitably to resentment, resistance and sometimes to rebellion.

But wait. In some ways, boys and men really are victims. This is not an ideological claim. It’s an observable and demonstrable fact that society must take seriously for the good not only of boys and men but also for the common good of society itself. And yet seeking truth - not being a postmodernist, I can use that word without blushing - is not enough to solve the titanic problems of any Western society in our time. It seems to me, therefore, that men have not only the right but also the duty to acknowledge their own plight and do something about it - if not for themselves then for their sons and for society as a whole. And yet I don’t recommend victimology as a worldview. Men should avoid that beguiling temptation. Even women are beginning to reject it. Society is already reacting against it. I deplore that profoundly cynical worldview on both moral and intellectual grounds.

JB: I very much like the term “linguistic inflation”, which I first read in Legalizing Misandry (2006). I think it’s a good description of what has happened to the concept of ‘masculinity’ in recent decades. Can you say a little more about linguistic inflation in relation to men?

PN: Well, consider the word “rape.” At one time, it referred to a specific act of violence: when a man forces his penis into an unwilling woman’s vagina (although it excluded the act of a woman who seduced an unwilling man into doing so). Now, legislators in many jurisdictions have replaced that word with “sexual assault.” This includes rape but also many other forms of coercion, some physical and others psychological or even financial. Consequently, it is now possible to enumerate more crimes of men against women than ever. And, of greatest strategic importance, it is now possible to convict more men than ever of crimes against women. Not everyone, however, is a lawyer. Not everyone distinguishes carefully between “rape” and “sexual assault.” In popular parlance, almost all encounters between men and women, even voluntary ones, can lead to charges of rape and be prosecuted as sexual assaults. These include initially friendly encounters, whether verbal or physical, which sometimes - due to clumsiness, say, or misinterpretation - can end up later on as accusations. For many people, therefore, the word “rape” has been inflated (overuse causing it to lose value as linguistic currency).

“Catharine Mackinnon argues cynically that all sexual relations between men and women are tantamount to rape, because male sexuality is not about sexual pleasure, much less about love, but about eroticized power”

Catharine Mackinnon argues cynically that all sexual relations between men and women are tantamount to rape, because male sexuality is not about sexual pleasure, much less about love, but about eroticized power - which is to say that men learn to be physically aroused by raping women (or other men). Similarly, she argues that female sexuality is not about sexual pleasure, much less about love, but about eroticized submission - which is to say that women learn to be physically aroused by being raped. In effect, therefore every sexual act between men and women constitutes rape. If so, then no woman could ever actually give her consent to sexual intercourse. Despite the legal and philosophical terminology in legislatures and courts, or maybe because of it, rape is by now often conflated in popular parlance with prostitution, trafficking, pornography, marriage, misogyny and so on. The only solution for women would be the equivalent of MGTOW: women going their own way by rejecting all sexual contact with men or even abandoning men altogether (although women would still require indirect contact with men, through sperm banks, for reproductive purposes). I find it hard to believe that many women will find this solution acceptable, although I do note here that some women have been promoting it on “social media” as a way of protesting Trump’s “misogyny.”

But one consequence of these efforts to “reimagine” the dangers of sex through linguistic inflation or deflation has been to undermine heterosexuality. Most people take the latter for granted as the mechanism that has evolved to ensure reproduction. They don’t always remember that heterosexuality, like all other features of human existence, requires extensive cultural support if it is to function both effectively and appropriately. Some feminists and gay or transgender advocates, however, go much further by classifying “heteronormativity” as a form of oppression. Long ago, Laura Mulvey wrote about what is now widely known as the “male gaze,” which causes men to “objectify women.” And they do. But there’s much more to objectification than that. This phenomenon is the sine qua non of sexual attraction and therefore of both intercourse and reproduction. If men were not physically aroused by the mere sight of women’s bodies, to put it bluntly, the species would never have evolved. And if men were prevented from being aroused in any way (such as prostitution or erotica), the species would soon disappear. Feminists who call this physiological and psychological phenomenon “objectification” make two assumptions.

First, they assume that men do not and perhaps cannot see women as real or whole people, that men must therefore see women only as objects, or toys, to be used for pleasure (or punishment) and then discarded. That’s tendentious, to say the least. If we take seriously the words of poets from many cultures since the dawn of literacy, we must acknowledge that sexual attraction is a very complex phenomenon, one that can have physical, psychological, social, moral, spiritual and even mystical dimensions.

Second, feminists often assume that women do not objectify men. That’s false. Women do so not only physiologically but also in other ways. Some women think of men, and treat men, as their very own trophies, wallets or sperm donors.

But the controversy over objectification extends beyond sexual relations. It seems safe to say, in fact, that daily life itself would be impossible if the standard for every encounter - even with sales clerks or business clients - were deep intimacy instead of objectivity.

““masculinity” refers to a gender system, the cultural system that elaborates on the natural given of maleness.”

Now, consider another frequently misunderstood word. As I define it, “masculinity” refers to a gender system, the cultural system that elaborates on the natural given of maleness. Similarly, “femininity” refers to a gender system that elaborates culturally on the natural given of femaleness. Why has every society since the advent of horticulture bothered to establish a gender system? For two closely related reasons. One is to enhance the allure of sexual attraction by emphasizing physical and cultural differences between men and women. The other is to bring men and women together on an enduring basis not only to ensure the welfare of children but also to establish a reliable division of labor for the entire community. Human behavior, unlike that of other species, has evolved to rely on cultural mechanisms to do what would otherwise be done automatically by natural ones (instincts). In evolutionary terms, after all, culture itself has increased the ways in which humans can adapt to changing conditions.

But the meaning of “masculinity” in popular parlance has been inflated (rendered intellectually and morally valueless) by extremely negative connotations. The word can stand alone, in some environments, because everyone assumes those negative connotations. In other environments, the word is preceded by a distinctly pejorative adjective such as “toxic,” “hegemonic” or even “traditional.” The first expresses emotional repulsion; the second expresses ideological theory; the third reveals ignorance of the countless variations that have governed masculinity, notably religious ones. Some ideologues have used this word in the plural, “masculinities,” to acknowledge the range of possibilities. But they often do so in order to set up a dualistic contrast between supposedly traditional and patriarchal versions of masculinity with their own feminist version. This is what happened when the American Psychological Association wrote its very first guidebook on therapy for boys and men (ten years after its first guidebook on therapy for girls and women), which made it clear that a major goal of clinicians was to make boys and men “for their own good” more like girls and women.

JB: You mention the complexity of free speech. Should free speech simply mean people saying honestly what they think and how they feel?

PN: There’s no such thing as an absolute right to free speech, John, because no right can ever be absolute. Most people agree on drawing a line between acceptable and unacceptable speech. But precisely where? Some people would draw the line at any words that might sound offensive or vulgar. Others would draw the line at any words that they consider incorrect (a.k.a. “misinformation” or “disinformation,” which can amount to anything that they consider politically incorrect). Still other people - and I include myself among them - would draw the line at any words that directly incite violence. This leaves plenty of room for debate between popular and unpopular points of view. Wherever you draw the line, however, you must apply it consistently. No double standards make any sense either morally or legally. This is what got Ivy-League universities in trouble several months ago. Their speech codes prohibited words that minorities might find offensive or threatening. When it came to the Jewish minority, however, the permissibility of words that advocate their mass murder would depend on their “context.”

JB: You say that there is a competition today between “the university as (a) an institution that encourages the search for truth or (b) an institution that promotes social change.” Can a balance be met between the two, or does it have to be one or the other?

PN: It’s not a question of balance. Rather, it’s a question of function. Professors, per se, are not preachers. To be more specific, scholars seek truth as an end in itself, not as the means to some political end no matter how worthy that might be or seem. And objectivity, to the extent that objectivity is possible in a finite world, has been the sine qua non of scholarship since the Enlightenment. But no one owns the truth that scholars find. Anyone can use it for any purpose. I’d say that there can be no such thing as justice, for example, if it rests on a foundation of utopian delusions or ideological doctrines. In other words, there’s a profound difference between justice and revenge. So, if academics do their own jobs well, they make it possible for others to create, sustain or defend just policies in the larger world.

“people can find ways of not seeing what they don’t want to see. […] Anomalies keep piling up and […] Eventually, it makes sense to abandon the old paradigm and develop a new one. [but ]Having invested very heavily in one of these worldviews, they find it very threatening or even impossible to question what has sustained them so far. Doing that would undermine both personal and collective identity.”

JB: You describe the theory of patriarchy as “a conspiracy theory of history” (an excellent phrase, which I think I first saw in Spreading Misandry) Henderson described patriarchy as a ‘luxury belief’ (another brilliant phrase), and Professor Eric Anderson points out that patriarchy theory is not actually a scientific theory in light of Karl Popper’s concept of fallibility. Why is it that this theory has so completely captured the minds of so many people? And is there any way that they will ever be convinced that it is just a delusion?

PN: Your question is about cognitive dissonance. What happens when the unthinkable happens? Everyone knows that people can find ways to see whatever they want to see. More to the point here, though, is that people can find ways of not seeing whatever they don’t want to see. And even when they do, they often find ways of explaining away whatever doesn’t fit their worldview. As Popper says in the context of science, that strategy doesn’t work very well in the long run. Anomalies keep piling up and require explanations that become more and more difficult. Eventually, it makes sense to abandon the old paradigm and develop a new one. And yet some people refuse to start over again. This happens to party leaders and stalwarts, for instance, on the losing side of elections. They generally explain the loss by blaming others, not by examining mistakes in their own ways of thinking.

Some forms of cognitive dissonance are profound and enduring. This is what happens sometimes to true believers, whether religious or secular. Having invested very heavily in one of these worldviews, they find it very threatening or even impossible to question what has sustained them so far. Doing that would undermine both personal and collective identity. To be blunt, true believers in any worldview, whether that of a traditional religion or a secular ideology, are unlikely, no matter what the cost, to consider ideas that might lead them in new directions - which would lead them to become heretics or apostates.

And yet, cognitive dissonance sometimes leads eventually to richer insights than would have been possible otherwise. This is what happened to the very early church. Jesus had taught the disciples to expect his return from death almost immediately, ushering in the Kingdom of God. This didn’t happen in any obvious way; daily life went on as usual in that corner of the Roman Empire. But theologians eventually explained that the Kingdom of God had indeed already begun, not materially but spiritually. With the Second Coming of Christ, which everyone would witness, a new cosmic order (beyond the finite constraints of time and space) would complete the process.

JB: “This notion of collective guilt lies at the very heart … of every … form of identity politics”. I think that this is a crucial point. Can you give an example in relation to men and patriarchy, and perhaps explain how it plays out for other iterations of identity politics?

PN: The doctrine of collective guilt, John, amounts to a rejection of the most basic premise of moral philosophy in the Western tradition: that every people are capable of making moral choices (a.k.a. moral “agency”). We have enough freedom to choose between good and evil, which is why we’re accountable for doing so. This moral argument, however, has an ontological dimension. To be incapable by any innate criterion (such as race or sex) would therefore mean not being a moral agent all but either a superhuman being (angelic or divine and therefore incapable of choosing to do anything evil) or a subhuman being (satanic or divine and therefore incapable of choosing to do anything good).

Ideological feminists believe in the conspiracy theory of history, according to which men conspired in the remote past to oppress women by creating patriarchies. But they believe also that contemporary men sustain patriarchal cultures and for the same reason. This means, ironically, that even contemporary men are not, and cannot be, moral agents. On the contrary, they are, in effect, innately or ontologically evil - which, as I say, would make them satanic beings. Never mind that this makes no sense because it would mean that no one could actually blame, let alone punish, men for their wicked behavior.

Blaming men collectively for every conceivable form of suffering or evil, and punishing them accordingly, lies now at the heart of what was once called “women’s liberation,” then “the women’s movement” and now “feminism” (by which I mean ideological feminism). Not all women are feminists of either kind, but many are. And even though some feminists still rely on the rhetoric of equality, others have replaced that with “equity” in accordance with the prevalence of wokism (notably its critical race and gender theories). They’re convinced by now not only that women, by virtue of their innate status as a victim class, are innocent and morally superior to men, but also that men, by virtue of their innate status as an oppressor class, are evil and morally inferior to women. The consequence should surprise no one. Women have created a movement that has become astonishingly indifferent to men at best and overtly hostile to men at worst. Directly or indirectly, explicitly or implicitly, much of feminist ideology today promotes contempt for men (in particularly egregious cases, even for their own sons) or outright hatred toward men (which supposedly excuses denial of due process and vigilantism). My point here is that this dualism is precisely what we can expect from the notion of collective guilt (applied to men), especially when paired with the notion of collective innocence (applied to women). Most feminists would not admit their contempt for men. Many would not be consciously aware of it. But careful analysis of the historical record of feminism over forty or fifty years tells a different story.

“collective guilt is now central to all woke ideologies. These divide the world into innate victim classes and innate oppressor classes.”

Egalitarian feminists find it easier than ideological ones to deny this shocking accusation, because they have enough moral integrity to avoid any direct references to the collective guilt of men. But some would condone it in others, nonetheless, for several reasons. Maybe they find it politically expedient for extremists to “push the envelope” for women. Maybe they want merely to “level the playing field,” an unpleasant rhetorical means to the greater end of “women’s equality”. But maybe they believe that it’s “payback time,” which would make it only fair if men are victims of women just as women have been victims of men (an idea that would replace justice with revenge). Or maybe they actually believe that men have such godlike power that no hostility from women could actually harm them in the first place (an idea that is demonstrably false).

Image: Book 3, Sanctifying Misandry: Goddess Ideology and the Fall of Man.

But the notion of collective guilt didn’t appear out of the blue. As a form of dualism, it has a long history that has nothing to do with the recent rise of feminism. One example would be the Christian belief (rejected now by the Catholic Church and many other churches) that Jews were collectively guilty for the death of Jesus and will remain collectively guilty until they accept Jesus as their messiah, en masse, at the Second Coming. This idea found fertile soil, of course, among those who translated medieval theological anti-Judaism into modern racial anti-Semitism. But that was not the end of it. Applied to new targets, collective guilt is now central to all woke ideologies. These divide the world into innate victim classes and innate oppressor classes. Without the notion of collective guilt, there could be no such thing as “critical race theory,” “critical gender theory,” “intersectionalism,” DEI, affirmative action, reparations for slavery and so forth. And by the way, wokers still consider Jews “collectively guilty” by virtue of being “white adjacent” and therefore responsible for “settler colonialism” in Israel.

JB: You describe an historically “changing relation between maleness (the male body) and masculinity (its cultural interpretation)” with an increasing “separation of masculinity from maleness”. Can you explain this please, with an example or two? Does this relate to the idea that masculinity is inherently somewhat adaptable, or does it prove that masculinity is purely a social construction, as the APA appear to believe?

PN: Let me begin with a short answer and follow that with a lengthy explanation, okay? Masculinity and femininity are cultural systems and therefore, by definition, “adaptable.” Culture is not a thin veneer. Humans are hard wired to produce it. Culture itself, after all, is precisely what makes our species so much more adaptable than other species. But this doesn’t mean that gender scripts are somehow autonomous or that they have no relation at all to sexual dimorphism. The truth lies somewhere between those extremes. We do have some freedom from natural constraints to improvise, sure, but not enough to ignore nature or to indulge in fantasies such as transgenderism and even some forms of feminism without grave physiological and psychological consequences. Culture notwithstanding, we’re still embodied beings and therefore rooted in the natural order. Not all women need to become mothers or housewives, for instance, and some should definitely not do so. Not all men need to become fathers or soldiers, and some should definitely not do so. But both activities (among others) are necessary to perpetuate any community, so both require enough cultural encouragement so that most women are willing to become mothers (in addition to anything else) and most men are willing to become fathers (in addition to anything else) in ways that are likely to be most helpful for both children and the community. Anatomy is not destiny, but it’s also not good or bad luck.

Our earliest ancestors were scavengers. We have very little information about them, but we have no reason to assume that they had or needed to have elaborate or even primitive gender systems. More likely, men and women did, personally and collectively, whatever they could do, and had to do, in order to eat and avoid predators. Eventually, they became hunters and foragers. This introduced the need for some specialization, although we have no reason to assume that even hunting expeditions and defense against predators were confined to men. Women and even children could have participated by making enough noise to scare animals away or by setting traps for big game animals.

But this practical “egalitarianism” began to change with the advent of horticulture and almost immediately of agriculture. Most people, by far, were serfs and therefore at the lower end of a hierarchy. Both men and women did backbreaking work in the fields, although some tasks were usually done by men (such as wielding iron ploughs) and others by women (birthing and nursing infants).

But elite men and women were, almost by definition, those who did not work in the fields. Elite women still gave birth, to be sure, but they had servants or slaves to help them with other household tasks. Elite men no longer hunted in order to provide food (although hunting sometimes had a ceremonial function that defined their status as elite men). They did lead soldiers into battle, it’s true, but they relied on male conscripts to do much of the fighting (except when the latter had to plant or harvest the crops that fed everyone). So elite men still had distinctive functions that were related to the male body at least symbolically.

Lower-class men, on the contrary, did the heavy lifting, and still do, in the fields, the mines, the factories and the armies or navies. Some of these men now earn high status as athletes, but those activities are vestigial. Their contribution to society earns prestige and money but still amounts to nothing more than entertainment.

Middle-class men, however, have been in a more ambiguous position ever since the rise of cities and states. And every ancient agrarian society had a small but vital middle class of traders, artisans, shopkeepers, scribes, potters, tailors, administrators, priests and so on. The functions of these men had little to do with their male bodies. Women could have done the same things, and now do so. But they seldom did until very recently, because culture (gender systems) - not nature - classified some tasks or behaviors as masculine and others as feminine. Men could not nurse infants, say, and women could not become lawyers. But the identity of women who nursed infants, no matter how many servants they had, was directly related to their female bodies. Identity had a stable source. The identity of men who became lawyers or physicians, say, had no relation at all to their male bodies.

The historical pattern has been to define men of high status as those who rarely need to exert themselves physically, if ever, and therefore don’t rely for their masculine identity on massive muscles or physical stamina. This pattern persisted in Britain and many other countries until well into the twentieth century. To be a gentleman meant to live on an inherited estate, not to work in “trade” or even to work at all (although it was okay for them to earn money by gambling). World War I brought the gender system (and every other cultural system) into question. Young women of all classes, once legally protected partly by their natural status as potential mothers, suddenly gained freedom to earn money outside the home without sacrificing their femininity. But young men of all classes suddenly had to demonstrate their masculinity in the trenches precisely because they had male bodies (not, according to the law, because of any personal affinity for warfare). For them, nature and culture, maleness and masculinity, collided with a crash after centuries of moving apart. Their male bodies enabled them to make contributions that were distinctive, necessary and publicly valued, sure, but also made them disposable. Four years of trench warfare came as a shock from which the old order never recovered. Feminists were among those who saw opportunities to agitate for a new social contract that would improve the lives of women by rejecting old double standards.

A century later, though, men are still trying to establish a new social contract that would improve the lives of men by rejecting both old and new double standards. One possibility would be a social contract that still forces only men to risk their lives in wartime but also still promises men more privileges than women in peacetime. Another possibility would be a social contract that relies on sexual equality in wartime no less than in peacetime. Both would make sense, but neither is likely to find consensus. Stay tuned.

JB: You say: “who could have predicted the clash between transgenderism and feminism? The answer is simple: anyone who understands the power of a dualistic framework - that is, of organized hatred - to achieve political goals”. Can you explain that a bit more please? Is it more than simply a ‘divide and conquer’ tactic?

PN: I don’t think so. The clash probably came as a surprise to everyone, not as the result of any tactic. (Transgender advocates certainly learned from the political and legal strategies not only of feminists but also of gay people, and I doubt that they expected anyone in either group to oppose them.) What makes the rise of transgenderism surprising is a profound irony at its heart. After all, it emerged directly from, and relies heavily on, feminism. Egalitarian feminism had for decades promoted the idea that men and women were interchangeable for most practical purposes (apart from the ability of women to gestate and lactate, although technology could minimize even those differences); other differences amounted to no more than “social constructions” that had originated in “patriarchy” but could be either ignored or adjusted in the name of “women’s equality.” In other words, feminists had trivialized innate sex differences (the biological givens of maleness and femaleness) in order to emphasize, for political reasons, the cultural distinctions of gender (variable behavioral scripts ranging from some form of masculinity to some form of femininity). By doing this, they trivialized the natural order and the human body itself.

With that in mind, advocates of transgender ideology go one step further by arguing that being a man or a woman had nothing at all to do with maleness or femaleness (a distinction said to be “assigned at birth”) and everything to do with “gender identity” (an experience said to be personal, psychological and often “fluid”). The irony lies in one result of this ideology: the belief that physiological men who claim to have “transitioned” and become “women” have permission to make claims that place physiological women at a disadvantage or at risk. (The reverse claim, by physiological women who claim to have “transitioned” and become “men,” has less serious consequences for physiological men). Much more is involved than demanding recognition of new names or pronouns. “Transwomen” demand the “right” to play on women’s athletic teams, use women’s washrooms and, if necessary, serve time in women’s prisons. Failure to comply with this pretense can be a punishable offence. The wonder is not that some women go along with it but that any women do. Those feminists who oppose transgender ideology place themselves in direct opposition to that ideology - and not only to that one but in addition, by implication, to all of the ideologies that are closely allied with it by virtue of similar claims about “patriarchal” (or Western) science, reason, the search for objective truth and so on.

JB: I always thought that antisemitism came from the right wing, so was taken aback in the past year or two to find it coming very virulently from the left wing. You say, “DEI classifies Jews as “white-adjacent” and therefore “privileged.” Is it the case that antisemitism no longer exists in the right wing, or is it just relatively less obvious there at present?

PN: Oh, I wouldn’t say that anti-Semitism (or any other kind of racism) no longer exists on the Right. I would say, however, that anti-Semitism on the Right is far less dangerous than anti-Semitism on the Left, at least in the immediate future. I do so for three reasons.

First, extremists on the Left are relatively rich, educated, sophisticated, influential and well organized. On their side are the prevailing worldviews of liberalism, progressivism and wokism along with those who promote those worldviews: the most influential journalists, pundits, teachers, academics, lawyers, social workers, psychologists, judges, legislators, even entertainers. That could change and maybe will change due to the recent American election. But something additional would have to change before anti-Semitism subsides, at least in some Western countries: firm support on the Left for Israel and Jews. The Catholic Church since Vatican II has repented for centuries of Christian anti-Judaism, which had led to the secular anti-Semitism of Nazi Germany. And many Protestant ones have “rediscovered” their theological roots in biblical Judaism. So, some important sources of anti-Semitism on the Right are no longer “respectable.”

Second, anti-Semitism on the Left has mutated (at least consciously) into Anti-Zionism, which is, in turn, a variant of the anti-Westernism that underlies all ideologies on the Left. Before the Enlightenment and the French Revolution (which emancipated Jews), many gentiles believed that Jews were too alien for integration into the larger society. Now, many gentiles on the Left believe that Jews are too integrated - too educated, too successful, too bourgeois, too “white,” too Western. From this ahistorical point of view, they argue that the Jewish state originated as an imperial outpost of the British Empire and that the Israelis are therefore “settler colonists” in the Middle East. (Never mind that returning Jews in the late nineteenth century did not “take” or “seize” land from anyone. Rather, they bought it. Unfortunately, they couldn’t buy it from the local Arabs (who were tenant farmers), so they had to buy it from absentee Turkish landlords (most of whom lived far away in Constantinople.). Opposition to this or that policy of the Jewish state does not necessarily originate in hostility toward the Jewish people, it’s true, and anti-Zionism is not necessarily the same as anti-Semitism. But I suspect that it is indeed when Israel’s policies are the only ones that motivate implacable and relentless hostility in the name of international law, justice, compassion, human rights and so forth. This blatant double standard is, in my opinion, very revealing.

Image: Book 4, Replacing Misandry: A Revolutionary History of Men.

Third is the rise of jihadi Islam, a new and seemingly unrelated factor. Although jihadis in the western Asia have nothing whatsoever in common with any Western political movements, let alone those secular ones on the Left, they have discovered how to make allies of Western anti-Zionists - that is, the proverbial “useful idiots.” To some considerable extent - I don’t know the precise extent - jihadi movements (and governments) overseas are actively sponsoring anti-Zionist hysteria in Western countries, which means that Western anti-Zionists knowingly or unknowingly collude with them even to the point of glorifying Hamas and other terrorist organizations.

JB: You say: “The word that best describes identity politics in all of its forms, including DEI, is probably ’anti-Westernism.’” The term ‘toxic masculinity’ has been used widely in the media (possibly damaging the wellbeing of men in the process), but would you agree that masculinity is the opposite of toxic?

PN: Anything, no matter how worthy, can become toxic. Even love can become distorted, after all, and manipulative or selfish. Notions of masculinity (unlike maleness) vary from one time and place to another, usually in response to circumstance or communal need. But I’m not a cultural determinist. I do recognize that all forms of masculinity are alike in at least some ways. All are interpretations of, or elaborations on, maleness. And all of these allow men not only to attract women personally but also to sustain their communities in distinctive, necessary and publicly valued ways. (The same is true of femininity for women.) But I’ve already discussed that. Your question here is about current notions of masculinity in modern Western societies and how these are, or are not, like those of earlier notions.

As I see it, two forms of masculinity are now very unhelpful to everyone. One of these originates directly or indirectly in feminism, either egalitarian or ideological, and amounts to this: The only good or healthy man is an honorary woman. Transgenderism notwithstanding, men are not women. And most men don’t want to be women. Moreover, not all women want men to be women (something that members of the American Psychological Association, most of whom are women, would do well to consider if only in the interest of their female patients). Heterosexuality, after all, would not work without some recognizable difference between men and women. Trying to ignore these facts is most unlikely to make men healthy, let alone happy. On the contrary, doing so forces them to affirm themselves at the cost of repudiating other men. That’s a form of self-hatred, neurotic to the core on a personal level and divisive to the max on a collective level.

But the reverse, what ideologues call “toxic” or “hegemonic” masculinity, is surely no better than feminist masculinity. Yes, every society needs men (or women, in their own ways) who demonstrate courage, tenacity, strength and so on. Yes, men are likely (or more likely than most women) to take risks and offer leadership for the common good. Yes, many men would like to have more than one sexual outlet. But let’s not conflate those general tendencies with the specific rules and symbols of this or that gender script. Maybe I haven’t seen enough movies lately, but I can’t think of many that don’t feature men indulging in cartoonishly coarse or brutal behavior - even in comedic contexts. Never mind the grotesque parodies of masculinity that we see - not from one American political party but from both - on the news every day. That’s intimidation and fear-mongering masquerading as masculinity. Within living memory, though, there were more models of masculinity to choose from - not merely two, each a mirror image of the other.

It’s one thing to admire Gary Cooper’s Will Kane in High Noon (and ridicule every other male character in that movie for either cowardice or brutality), because of his physical courage but also his moral courage. He was a desperately needed mythical hero for his time (in the 1950s, during the McCarthy Hearings in Washington). But even then, he was not the only masculine ideal. In To Kill a Mockingbird, Gregory Peck’s Atticus Finch is quite similar. But he embodies moral courage more than physical courage (in the 1960s, when Americans needed a mythical hero to foster racial desegregation in the South). As recently as 1981, a very different kind of masculinity was possible. In My Dinner with Andre, Wallace Shawn plays an antihero. He’s short, fat and bald. Unlike his friend, he doesn’t look glamorous and can’t entertain anyone with stories of wild adventures all over the world, let alone explain them by quoting philosophers. But Wally makes up for his apparent inadequacies with patience, modesty and eventually with intellectual courage. Well, I’m not going to cite dozens of movies here to demonstrate my point, which is simply that defining “traditional masculinity” as inherently “toxic” makes no sense of a complex history.